Editors Note: This morning I saw the news about Canva raising a bajillion dollars and a 40B valuation and promptly saw some hot takes on ‘how its PLG driven’ - even though from what i’ve read / seen & discovered, its primarily driven by SEO & WOM.

I’d argue Canva is not ‘PLG’ if anything they marketing led (most PLG companies one could argue are the same) - it has a brilliant SEO but more so they saw a huge opportunity in the market for ‘light’ designers who did not need the full Adobe Suite. Their SEO strategy was around templates & design school. They executed relentlessly on a fantastic product. If you want to go deeper, highly recommend this.

Figma & Sketch did the same for product designers. Great products naturally drive WOM. It helps they were selling to SMBs & ICs so they could have a free plan, little or no sales infrastructure or complexity.

What is interesting is no one talked about MailChimp exiting for 12B because its PLG (seems like everyone who has a free plan is suddenly PLG now). If you ask 10 people what product led means - you’ll get 10 different answers. No not counting the content marketing by a VC firm here.

This is something I’ve been thinking for a while. Most products (with exceptions) start their life selling to a small business or IC market (call them prosumer to borrow from camera terminology - RIP Prosumer cameras).

Some prosumer (like productivity software) lend themselves to stronger network effects (I share an Asana project or a Loom video or Airtable base) - they *multi-player* products but low overhead & complexity. Making them free to use helps spread it organically and drive WOM. Especially when selling to SMBs they tend to have strong organic growth.

Eventually products move upmarket. They either want to go upmarket (larger deal sizes, better margins, longer contracts etc) or the SMB customers they sold to ‘pull them’ up market i.e. Hubspot customers getting bigger & needing more complex solutions as they grow.

But as you move upmarket - the complexity involved also increases. You are not longer *just* selling to users. You have to navigate more complex buying cycles, budgets., agendas & objectives. A great example of this is Notion, Airtable (more on that below) and Webflow.

I am a Webflow customer. I pay them $/year (standard basic plan) but there’s also a huge opportunity in front of them to go after larger companies. WordPress already does this. WordPress is open source & commercial - it runs a 40% of the internet (a staggering market share) and they have enterprise customers like Salesforce, Facebook, NYT & NYP under the WordPress VIP program - their managed service & white glove enterprise product. Automattic (the company behind WordPress, Long Reads, WooCommerce, JetPack, Akismet etc) It has 284 people who work in sales. Automattic is an interesting case of open source / commercial hybrid like RedHat & dbt (yes its lower case).1

Larger orgs move slower & have complexity by design. Managing a 10 person team is very different than managing a 50,000 person company. All those layers that slow down decision making also helps to make sure nothing ‘breaks’. I would not want my bank to ‘move fast and break things’. Hence the way they buy software & deploy software is different. You can attach a ‘free’ plan to Salesforce but to actually get value out of it you need more then a great product onboarding experience.

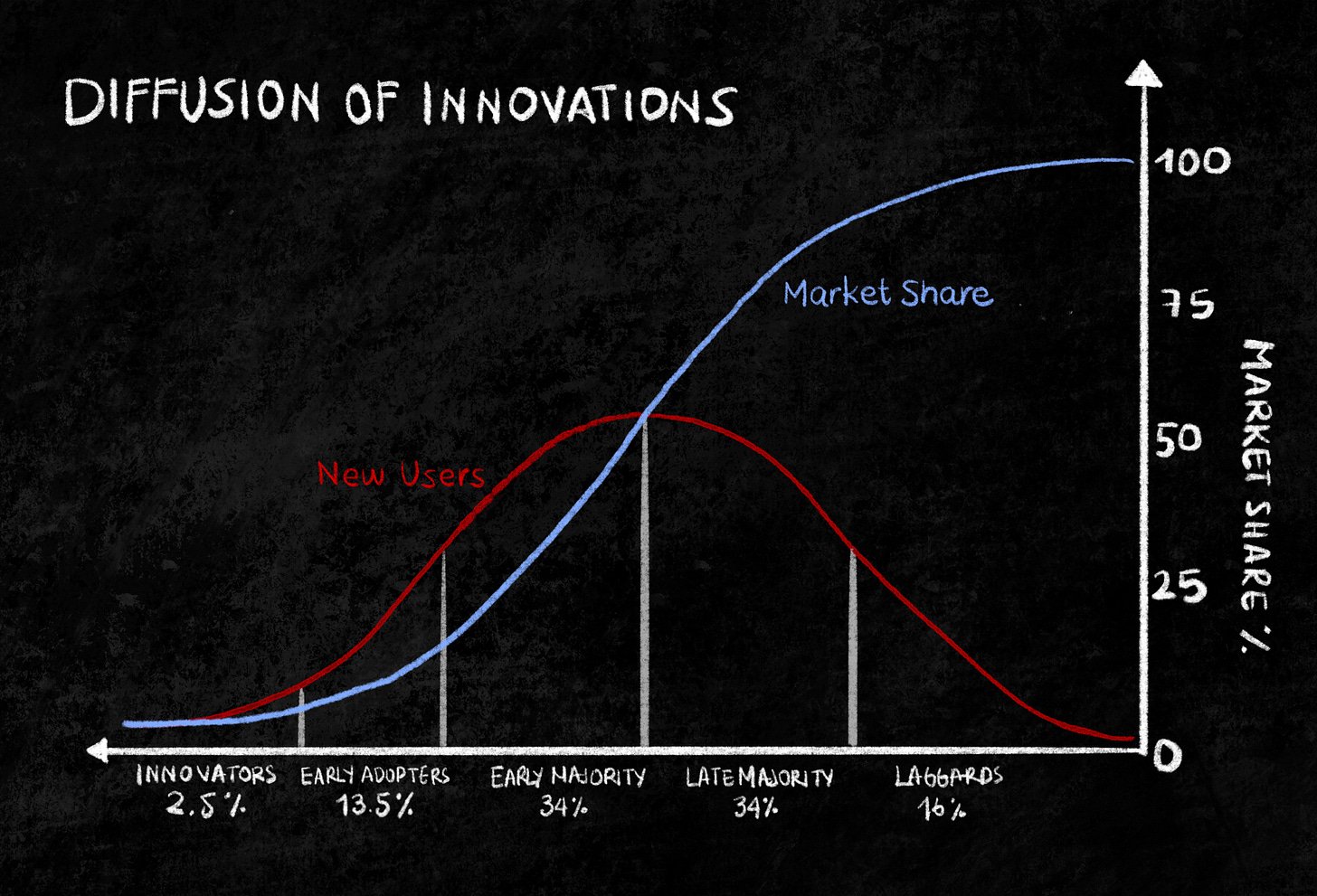

GTM & Technology Adoption Lifecycle

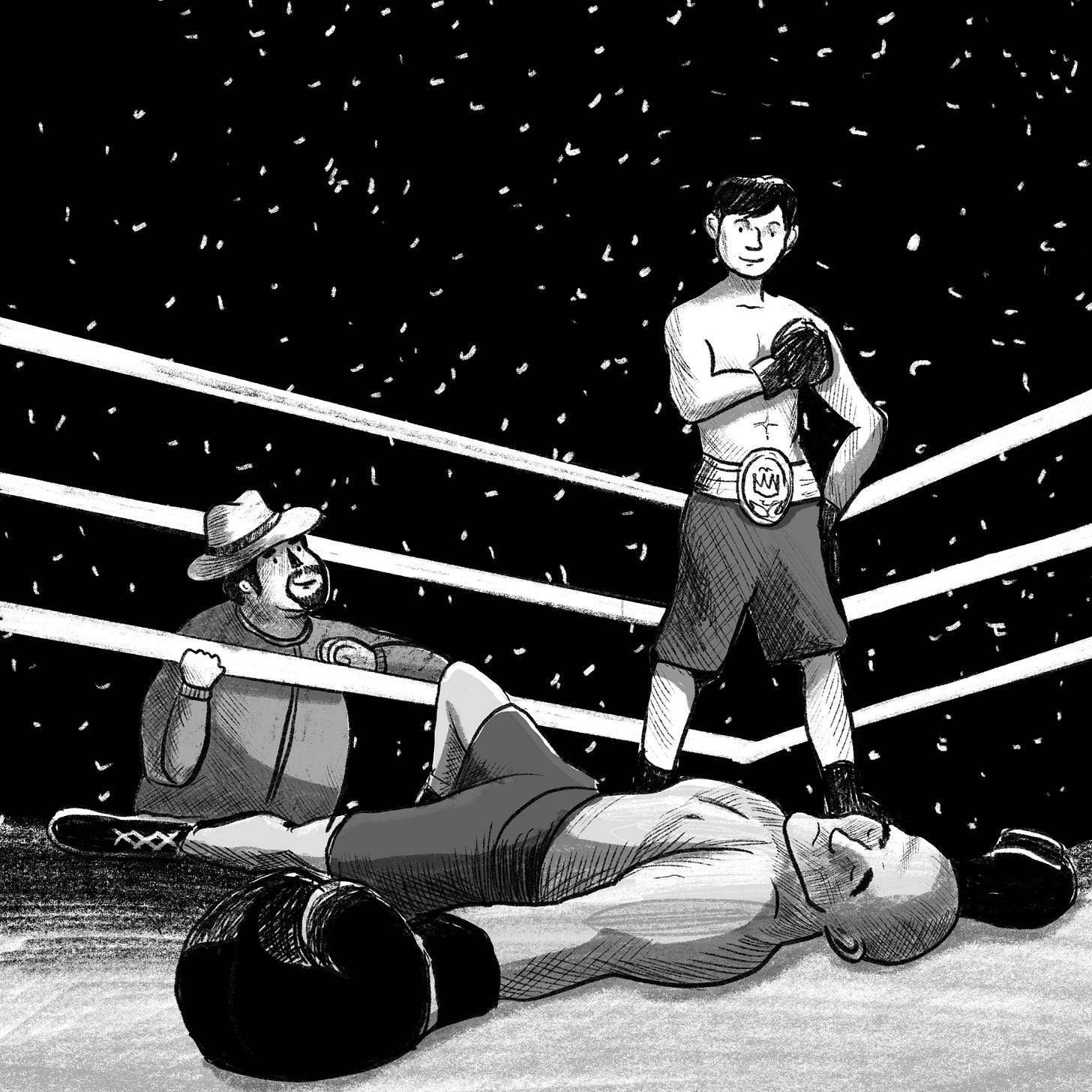

"Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth."

Mike Tyson.

In the startup world, where we seem to think of ourselves as analytical and rational creatures, we are still bound to fall prey to our own psychological biases. One of the most popular biases that entrepreneurs, particularly product first founders have, is that a product will sell itself.

But, history teaches us otherwise.

We are all familiar with Slack.

"This is how we have grown so far, and we'd like to continue this forever, which is — people really like it, and so they tell other people about it, and then other people start using it," what a powerful and symbolic quote by Stewart Butterfield (Slack) back in 2016. It seems that the GTM strategy was to leverage their power endlessly - in other words, Butterfield thought the product would be enough, forever.

Yet, recent history shows otherwise, Slack ended up selling to Salesforce for 27.7 billion. Something that has industry experts divided but is a sign that selling to startups and SMBs (and that can be freemium aka product-led) is not the same as selling to enterprises. Bottoms-up GTM motions and self-serve user experience are essential but, in most cases, not enough.

In a way, Slack got punched in the mouth. And, even though most people we know love Slack, it turns out that innovators and early adopters behave differently than the majority of the people in the technology adoption curve.

(Alejandra should probably create this image from scratch)

Conventional wisdom says we can create a disruptive product that forever changes culture. But, several of us might overlook the GTM (Go-to-Market) part of creating a product (how you get the product into hands on customers) and what it takes to penetrate a market and increase your market share.

Think about how a large Fortune 500 could use and adopt Slack with a bottoms-up motion.

It will probably never happen.

Even though the users might love it. For org-wide adoption, there are several gatekeepers, processes, and policies that do not allow individuals or specific teams to adopt new technologies without buy-in. There are several reasons for this, but mainly security and safety (avoiding risks) tend to be the most crucial impediments. You would not want your bank to buy non-secure software (risking a data breach). So while it might be frustrating to see bigger organizations move slowly, there’s often a risk tradeoff involved in the situation.

This is one of the reasons MS Teams has a 41% market share vs Slack 18%. Microsoft already has a foothold in the mid-market / enterprise segments with Windows OS, Office 365 & Skype for Business. Once they released Teams as a free product to existing MS Office users, it was expected the adoption would take off. IT, Finance & Executive Teams at F1000 already trust and use Microsoft. Microsoft has a whopping 44,000 people in sales to sell, service & support enterprise scale revenue engines vs Slack at approximately 1000 sales headcount. Maggie Hott (2015) who was the first AE at Slack talks about it a little on Inside Intercom here.

The difference b/w Slack & MS Teams is more than just sales headcount though. It starts with the markets they went after. MS Teams is entrenched in the ‘large org’ market. It is stable, secure, and it works. It is bundled with other useful ‘office’ software like Word & Powerpoint giving it strong network effects - for example, you need to download excel to open an excel file. Excel is probably one of the most successful pieces of software ever & the OG no/low code tool. There’s a reason why despite all the new ‘excel killer’ apps like Airtable, Notion, Coda - no one has been able to kill of excel yet - no not even Google Sheets. And, to tie it to the GTM strategies and its competition with other software in the category, once you're using MS Teams there’s little reason to rip it out and replace it with something else simply because large organizations already trust Microsoft.

In other words, as Slack started to take off in a more remote-friendly world, it was relatively easy for Microsoft to launch Teams to an ‘existing base of customers’ to starve off Slack from the enterprise market.

It is much more convenient to buy from a company that offers safety than from a company that offers innovation. The values are different, and therefore, the strategies to sell each segment are also different.

Slack started off selling to other startups & technology companies who are more willing to try new software. They are the innovators and early adopters who provide feedback, accept buggy software and don’t balk at unproven products. The early adopters are also the group who want to try things ‘hands-on’ - they don't like sales, process, and have a higher risk tolerance.

In other words, innovators and early adopters are the first ones to try new products because they are also the ones pushing and creating new products and categories. They might be the kind of people that might even provide valuable feedback and will help you scale the product to the rest of consumers. Nonetheless, it is also crucial to keep in mind that they are also the kind of people who are comfortable with changing their ways and adopting new technologies, not necessarily the ones that can push your product massively. For that, the tech adoption chasm must be crossed, and you need a GTM strategy that tackles that from the get go.

We all want to believe in the underdog, the sweet product that changes a category forever because it is impressive and its use is frictionless and solves lots of problems. But, it turns out that in most scenarios, a sales process is required to push the product beyond the early market. Not because the product itself does not solve a crucial set of pain points for users, but rather, as we mentioned above, the way innovators and early adopters incorporate new technology into their lives is radically different from the rest of the market (innovators vs early majority).

Even successful companies such as Atlassian that changed categories completely rely on much more than their "great" products. - check out our entry on Atlassian to learn more.

So, to get back to the main subject of this post, when should you take your GTM strategy to the next level and implement a sales engine for your organization?

Quick answer - whenever you are ready to cross the Chasm.

Post-chasm sales lifecycle.

— Liam Mulcahy, Director of Sales GTM, Unusual Ventures

If you ever had the chance to work at an Mid-market, or Enterprise org, you might have experienced the pain of having to convince gatekeepers whenever you try to implement any new tech into your workflow.

Be it something small and without friction like Calendly or something more robust and needing an onboarding process like Salesforce, adopting new tech tools is hardly ever a frictionless experience for about 80% of the people in the adoption curve.

On Lenny Rachitsky Substack (highly recommended), particularly in his GTM motions entry, he covers how some of the most popular B2B SaaS startups have approached their GTM strategy.

He mentions five key takeaways among his findings, from which we will focus on two:

100% of product-led companies end up adding a sales team, if not going sales-led completely

Everyone moves upmarket—few go the other direction

His first takeaway, and perhaps the most essential for this piece, is that several SaaS startups at some point realize that to cross the chasm, you need more than a product. Innovators and early adopters consume products differently than the rest of the tech adoption curve, and they amount to only about 20% of the overall population your product could potentially reach.

Impressive digital products are highly abundant in a networked economy. And, the problem of relying on PLG aka freemium alone is that you might lose valuable traction (the other 80% of the adoption curve) required to keep your startup afloat.

Sales matter. A lot. Not because they bring clients (that is an outdated concept of what sales do), but rather because they are the ones that are in charge of strategizing, executing, and ultimately penetrating markets that are much harder to influence and capture.

An exciting example of implementing a sales process without having an entirely devoted sales team is what David Peterson shares on this fantastic thread. To summarize, back when he worked at Airtable, he and his team noticed individuals within organizations that excelled at using the software. And, taking advantage of their motivation and skills, they developed courses and support systems to turn them into product influencers within their organizations.

As he mentions, it worked pretty well. Turning "10 users to 1000 users in 1 year…without any referral hacking or network effects."

Just as David mentions, "I think there is a coherent strategy here (much more coherent than PLG!) worth capturing…" we also think a concrete sales strategy, once again, is essential. But, not the annoying salesman we have in our collective imaginaries, but rather the helpful person that has something so valuable and exciting to say that it captivates everyone's attention and ultimately leads to change (for example, using Airtable) in an organization.

His second non surprising conclusion is that everyone moves upmarket, and few go the other direction. This is the reflection of the predominant culture and ideology behind the creation of products that scale quickly.

We have learned from startup lean development models that building, learning, and failing fast with a niche is the best way to create fantastic products (unlike the traditional market research/full-scale deployment methods). A startup and any SaaS is an unstable environment in which adapting and understanding what your users need even before they know it is crucial for growth. But, even though we are all familiar with this framework, when moving upmarket, the goal shifts from learning quickly to earning trust and developing the RTBs (reasons to believe) that stakeholders need to embrace your product.

Doing so will allow you to reach more potential clients, including corporate accounts, and overall just achieving the growth that takes a startup from the "Start-up" phase to the "Scale-up" phase.

Plus, as the research by Marc Thomas shows on this tweet - 0 companies are using freemium model after crossing the $50M growth stage. This phenomenon cannot be a coincidence. PLG strategies lose traction once you want to move upmarket. On that very same thread we even found a tweet by Kyle Lacy CMO of Llessonly where he specifically mentions that “Free trial dropped off after $3M.”

Honestly, this move to stop relying on PLG seems to be a pattern for success.

Or, as it is beautifully explained by Jimmy Daly in Animalz:

If you genuinely and exponentially want to grow your SaaS, this is pretty much the way to do it.

But, why is it that regardless of the evidence that this catapults growth, it appears to be a much more arduous task than most founders anticipated? Why is it that a PLG strategy does not seem to work to climb upmarket?

Culture, the key to crossing the chasm.

What? Culture? Are you serious? Yes. We actually are.

The amount of literature, articles, guides, and resources to understand and create a GTM strategy is already out there. The number of examples that prove PLG eventually becomes sales-led is already out there (see links above).

But, what is actually missing from the conversation is the principle behind this phenomenon. And, ultimately, the reason why the GTM strategy has to be sales-led or at least sales assisted if your SaaS wants to climb upmarket. Truth be told, product leaders face a much more difficult monster to slay as they leave the innovator and early adopters section of the market.

The monster: skepticism.

Creating SaaS digital products for B2B segments allows founders and leaders to think that PLG is the holy grail. After all, if you are selling to tiny and medium businesses and startups, the amount of bureaucracy tends to be light, therefore, enabling quick product adoption cycles.

But, conquering dinosaurs (more traditional potentially larger businesses) is a whole different story.

The challenge in GTM strategies for SaaS B2B companies crossing the chasm is that success is no longer about exclusively creating the best product of the category but about gaining trust in bureaucratic and complex business ecosystems.

And, as such, you may need a team of individuals that help you influence organizations both internally (like the Champions in the Airtable scenario) and externally like Hubspot. Hubspot’s genius marketing was building website grader. It acted like a lead generation tool - SMBs come in and ‘grade’ their website - they get a report with opportunities & how Hubspot could solve for it. But more thanthen that - it was used by Sales to sell the promise of Hubspots platform:

“In early days of @HubSpot, once we booked a sales call, the first thing we did was create a custom demo portal for the prospect.

We'd gather URLs of our prospect's competitors & the search keywords they rank for.

We'd enter in best guesses if prospect didn't supply them

Once we got a prospect on a call, we'd immediately show them "competitor grader" in the custom demo portal we created. It was a simple table with a few columns. The first column was the grade for each URL entered. Theirs would be in the top row and competitors below that.

Prospects would look at the grades & feel embarrassed, frustrated (or some other uncomfortable emotion).

It was better than any words a marketer could put in an email or a salesperson could say

Their next logical question was, "How do I fix the fact that I suck?"

Of course, your product has to be an MVP that is highly user-friendly and intuitive with minimum friction. Still, beyond that, you need to gain the trust of stakeholders that can help you move upmarket and ultimately help you increase revenue.

No startup ever was successful by limiting itself to pushing its product to innovators and early adopters (20% of the overall population). Plus, just because you happen to go through an accelerator program with people like yourself who are early adopters and love trying new things (Think Y Combinator), does not mean your product fits or can adapt to a mature market/user.

In other words, the focus of customer acquisition has shifted from exclusively capturing individual users via product to finding key stakeholders that can help SaaS signing contracts with larger organizations via sales.

It is not that the product is no longer at the center. Product-led growth is crucial because it forces entrepreneurs to focus on creating the most ideal experience for users. But, beyond that, there is an additional need to create an organized revenue system that allows fast-moving startups to access and influence slower enterprise business ecosystems. For example, in this entry, we can see how Atlassian's GTM team changed the equation to understand sales. And, it worked.

There appears to be a shift in the understanding of growth as the article on the previous hyperlink also mentions. "Growth is owned by marketing and product, not Sales. The funnel would begin through campaigns, self-service signups, etc. Sales teams do not do outbound motions or have qualification calls."

Sales switches from being the cold-calling lead generation machine to a strategic and cultural branch of the startup that allows execs to undergo a paradigm shift and push for new technologies within their organizations.

Therefore, what is required to conquer the latter stages of the tech curve is to leverage the power of social movements. Identifying your allies within organizations that will vouch for your product and ultimately lead you to gain large contracts.

Large contracts = tons of users.

The essence of a freemium strategy (an excellent product) combined with a sales-driven system is the key to developing successful GTM strategies for SaaS trying to access mature markets. The evidence is there, the literature is there, and now, the principle (from skepticism to trust) is more explicit.

Selling to enterprises and larger organizations is not only about having a great product; it is about creating a trustworthy culture around your product that allows stakeholders to vouch for you and provide larger contracts for your SaaS startup.

Do not get punched in the mouth, believing your product will endlessly sell itself. That strategy does not work for all users and exponential growth. And, being the underdog that changes a category just by having a great product has been proven to be a myth, as we discussed in our Atlassian essay.

Lead the way and make sure you have a GTM strategy that goes beyond innovators and early adopters. Shift your view of sales as a lead qualifying machine to a strategic team that focuses less on transactional deals and more on strategic ones for the company.

Self-service products can only grow so far. Or to put it more blunty: